If I could predict the future value of a huge land mass, say, about 12 billion mostly urbanized square feet in a First World country, would that interest you? Your answer might be both “yes” and “no.”

We think of investments in two broad classes: Financial and Real Estate. For simplicity I ignore rare art, precious metals and professional sports teams, all of which are also investments. Devotees of the stock market brag about their passive ownership, cringing at the idea of talking to tenants and fixing toilets. Real estate investors stress the word “real” as in tangible, solid, fixed in supply and location.

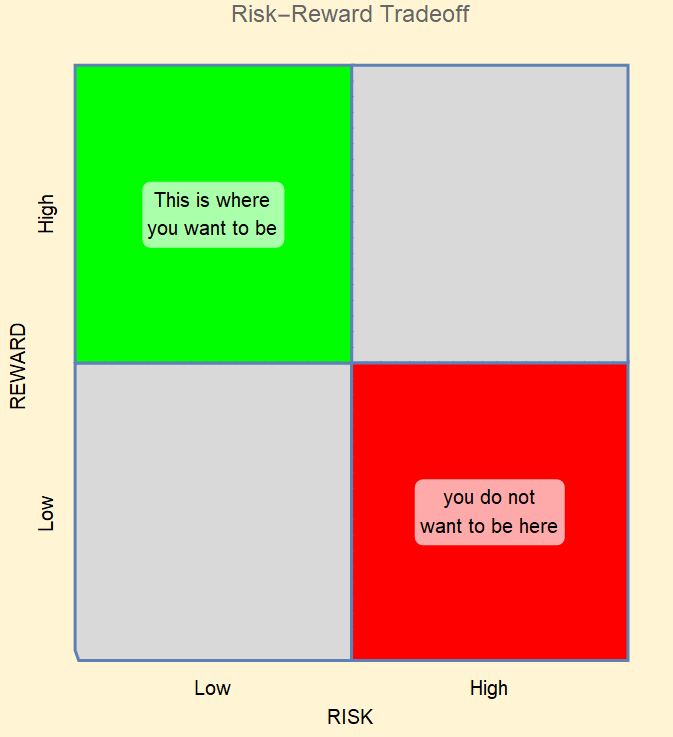

In either case we are after the safest return we can obtain. The words “safe” and “return” have a troubled relationship. The connection is not perfect but we think of higher returns coming at the cost of higher risk. Illustrating the Risk-Reward Tradeoff looks like this

Developed countries with established laws governing property rights are safe harbors. Real estate located in the US, and the US economy in general is, so far, viewed as stable by comparison to much of the rest of the world. Real estate values in Syria are likely falling. The Damascus Securities Exchange is not doing well, either.

Land is a solid investment only so long as governing bodies residing upon that land are sound. What trades in the market are the rights to occupy and use land. To the extent these rights are not enforced, compromised, ill-defined, subject to confiscation or armed conflict, the value of land falls.

So, our question is: How do we measure or predict future instability? A case study unfolding right now is Hong Kong. There is a computation that produces a curve describing all the combinations of return and risk. This curve can be calculated (I will spare you how) from prices at various points in time. It turns out that the location of that curve matters. Hong Kong price data for real estate over a thirty year period allows us to make those calculations. The idea is that all future risks are “priced in” such that the current price reflects a common, fairly accurate, sentiment about future price. Hong Kong is in turmoil today. What you see below shows how, long ago, the market measured and predicted the events transpiring now.

The plot below starts with red and green curves, each initially for the same ten year period 1984-1995 (red is behind the green for that one initial frame). As we add subsequent years’ data, the curves separate. Notice what happens as 1997 approaches and afterwards. For reference, the “good old days” green curve, fixed for the early years, remains where it once was. Beginning in 1998 the red curve extending into those later years retreats to and remains in the lower right quadrant, a location where you do not want to be (for time reference as the plot changes, focus on the third line at the top in the plot label). If you do not know what happened to Hong Kong in 1997, check this link.

The market is telling us: Beware, large neighboring communist state encroaching. Thus, fixed in location can work against you when you cannot export your asset out of a hostile political environment. Is such an outlandish result possible in the US as the trend toward socialism expands across our country? Perhaps. The numbers are out there to test that theory.

Capitalism can exist without democracy (think: black market) but the converse is not true. Watching events unfold in Hong Kong alongside events in this country portends ominous clouds on the horizon for both countries. The difference is that Hong Kong’s problem is imposed from the outside. Ours is homegrown.

I began with a question for which the answer is both “yes” and “no” followed by evidence leading in the direction of “yes.” However, I suspect some readers - including some in China - would say “No, I do not care about 12 billion square feet in Hong Kong. I care about the value of my 2,000 square foot house.”

Fair enough.

The way to think about this problem is similar to how we think about insurance companies and mortality tables. Start with 100,000 non-smoking males age 50 alive on January 1. Your insurance company can tell you with a high degree of accuracy how many will be dead 365 days later (unfortunately, they cannot tell you their names). Note (again!) the conditional probability. I specified non-smokers. I specified males. I specified a particular age. All of these conditions strengthen my ability to predict. Let’s focus on smoking. If you do not smoke today you have some life expectancy based on your age and gender. If you take up smoking you probably shorten your time with the rest of us.

So I can’t tell you what your house will be worth in ten years. But I can tell you that continuing to allow government to acquire more of your wealth and property rights is the national economic equivalent of starting a six-pack-a-day smoking habit. So, if all houses drop in value you may expect yours will also. Incidentally, for value we need to use real (inflation adjusted) dollars, not those phony Federal Reserve Notes being printed by the trillions as you read this.

Real estate is a good investment until it becomes a place where you do not want to be.

The numbers are there. Others have gone before us. Prediction is not hard.